I find this book really interesting, most in the:

PART 4: implementation phase

https://www.lunanh.com/post/creating-conflict-infrastructure-a-group-workbook

p 75-80

I report here the content of these 5 pages:

Part 4: the implementation phase

At this point the plans have been laid out. Collectively, you understand the processes and systems you’ll use to address conflict, who can access those systems, and what types of conflicts/issues these systems can and cannot address. If you decided to have written policies/protocols, those have been

drafted and approved based on your internal decision-making processes. If you decided to offer conflict interventions or processes (such as crisis response, healing circles, or mediation), you’ve skilled up to be able to provide those and you know who will respond and how they will do so. If you’re dedicating specific resources to addressing conflict, those resources have been secured and are ready to be used.

You’re about to set the wheels in motion, so all that’s left to figure

out (and do) is…

4.1 How are we sharing with relevant people and communities that policies/protocols are now active?

Why the means of sharing information is important: Too often, organizations

will develop policies that members are expected to follow (e.g. agreements to

communicate directly about interpersonal conflict or file a report to leadership), but those policies are never made clear to the people they impact. Consider communicating in a format other than a long e-mail thread with a pdf attachment or through a slack channel—it may be valuable to hold a dedicated potluck or celebration of finally reaching this milestone of addressing conflict head-on, where the policies are explained, the hope for positive impacts on the organization are made clear, and involvement with the policies are encouraged and welcomed.

4.1.1 How can people access those policies/protocols in writing, to refer back to as need arises?

Why access is important: Policies can easily be forgotten and then brought forward only after a crisis arises and someone is being chastised for not following protocol. Consider including easily readable, easily understood written documents in multiple places where members are likely to look when they need information about what they can or should do when conflict arises (such as the org’s website, slack channel, handbook, etc.). If you are a multi-lingual organization or know there are people in the organization who cannot read or see digital documents, make sure these materials are accessible to everyone. If there are procedures to follow, consider making visual illustrations of workflows and processes that are easy to understand.

4.1.2 How and when will we reflect on these policies and protocols, to make adjustments where needed?

Why reflection is important: Inevitably there will be holes in the policies

you created while things were calm. New dynamics and situations will

arise, that don’t quite fit into what you’ve created. Or, you’ll find that the

policies are producing a different outcome than what you originally

intended. Making sure you dedicate specific time (3-months, 6-months, 1

year, etc.) to reviewing how things are going, will save you from the

headache of trying to force people to fit into the policy, rather than the

policy fitting the needs and experiences of the people.

4.2 What means are we using to communicate with relevant

people and communities that resources and conflict processes

are available? And what information are we sharing?

Why communicating is important: People who have no experience with third-party conflict intervention (mediators, crisis support, facilitators) are likely a little suspicious, cautious, or anxious about accessing those supports. Further, people who do have experience may have only oppressive experience (e.g. court-mandated mediation or police-led crisis response). Know that people

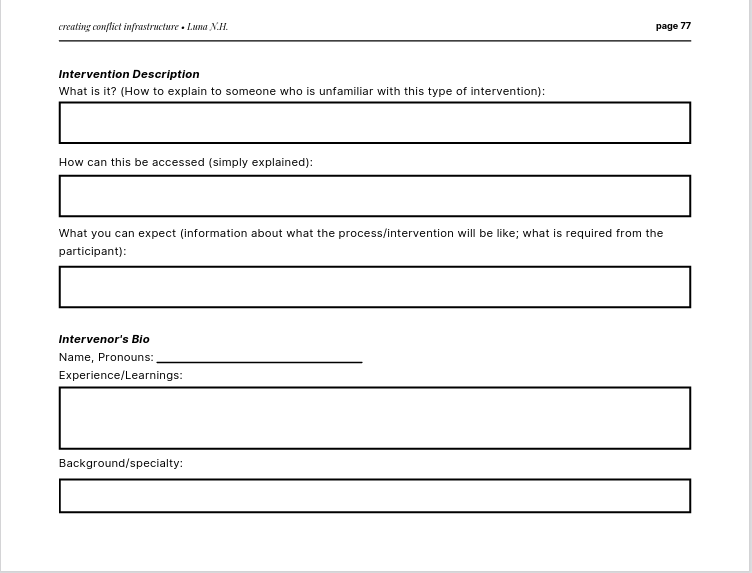

may be starting from a place of mistrust. Not only is it important to make sure that the people who can access your supports know that they exist, it’s important to share any information which may make them feel safe and confident using those supports. For example, consider: sharing images and bios of who will actually be showing up, with their training and experience; the values/principles being used to guide support; the rights/protections extended to people who access support (such as confidentiality, self-determination); and being very explicit/forthright about limitations (such as who cannot access the services or issues you’re not able to address and why).

4.2.1 How are people reaching out to us to access those resources and processes?

You may have discussed some of these options in 3.2.5. Here, consider how

those choices are working as you implement them. For example, if you’re

offering mediations—How do people request a mediator? By e-mail? By

phone? By online form? Is there paperwork to fill out? Can they communicate

anonymously or confidentially if they just want information?—reducing

barriers to access should be the goal to this process and making sure that as

you implement, things are working the way you wanted/expected (and making

adjustments if not).

4.2.2 How and when will we reflect on how the means of accessing the resources and processes is working for the people who need them most?

Why reflection is important: Similar to above, you’ll likely run into issues

where people aren’t reaching out or the way things are set up cause obvious

issues (difficulty keeping confidentiality, overburden to the intake person,

people are saying they don’t know how to initiate things, etc.). For example,

when I started practicing I only had an e-mail option with a standard form.

After a while, it became very clear that people were hesitant to send a blind

e-mail with their personal information. So, now I offer a virtual intake (no

paperwork required), e-mail, or an online form, so that folks can pick the

option that works for them. Setting a specific time to track data on the

requests you’ve received vs. your perception of what people want/need, will

help to adjust to what folks actually feel comfortable with.

4.3 What is our initial capacity to take on cases?

Why initial capacity matters: There’s a learning curve at the beginning of any new project/program, and the emotional/intellectual burden of doing conflict work is always more significant right in the beginning. It will take a while to get your bearings. Consider scaling up very slowly, with plenty of time to reflect and shift things as you learn more about yourselves as practitioners, the community receiving the support, and the kinds of issues coming up. Burn-out can lead to loss of trust, if facilitators/intervenors are found to be checked out, unreliable, or not equipped to be responsive to the people they’re working with. It’s very hard to come back from loss of trust—so protect your relationships by easing into things, even when it feels urgent to address immediate crises.

4.3.1 How will we know we’re ready to take on more?

Why readiness is important: Often people think of a “scale- up” in terms of a timeline, such as “In year 1 we’ll take 10 cases and in year 2 we’ll take 20 cases”—this is a capitalistic mindset, where “success” is defined by quantifiable growth.

Instead, think about scaling up in terms of relational health. For example, “I’ll know I’m ready for more cases when: I’m feeling confident with my current case load, I feel energized rather than drained by my sessions/interventions, and the people I’m working with feel confident in me and my responsiveness.” And maybe also consider some boundaries, for example, “I will not take on more cases if it means I have to work/facilitate/intervene after 7pm or on weekends.” Understanding this ahead of time and communicating with each other what these guideposts are, will help to subvert resentments, burdens, and burn-out.

4.3.2 How will we know and communicate that we’ve reached our limit?

Revisit the conversation from 3.2.9.1. How does this feel in

terms of scaling up or down in the beginning of the work?

Any additional nuances?